Laissez Dangier faire tous ses effors 3v · Busnoys, Antoine

Appearance in the group of related chansonniers:

*Dijon ff. 111v-113 »Laissez dangier faire tous ses effors« 3v · Edition · Facsimile

*Nivelle ff. 27v-29 »Lessez dangier faire tous ces effors« 3v Busnois · Edition · Facsimile

Other musical source:

*Bologna Q16 ff. 122v-123 »Layses moy« 3v · Edition · Facsimile (pict. 250)

This page with editions as a PDF

Editions: Busnoys 2018 no. 42 (Dijon – faulty).

Text: Bergerette; full text in Dijon and Nivelle; also found in Berlin 78.B.17 f. 111v, ed.: Löpelmann 1927, p. 189; in Paris 7559 f. 51v the refrain appears in a rondeau, ed. Bancel 1875, p. 107.

After Dijon:

Laissez Dangier faire tous ses effors, Amours m’a fait par Bel Acueil douceur et de ses biens a souhait m’a fait seur Male Bouche n’a pas tousjours bon mors laissez Fortune a tout sa roe aller, laissez chacun a volente parler, car il aura, qui me nuira, bon corps. |

Let Danger make every effort, Amor pleased me by Fair Welcome and by his gifts has made me so safe >Slander does not always have virtuous manners, Let Danger make every effort, |

Some differences in spelling between Dijon and Nivelle.

Evaluation of the sources:

The main scribes of Dijon and Nivelle chansonniers have copied the song from two very closely related exemplars. There are minor differences in spelling in the poems and in the use of coloration and in a few details, and in Dijon we see a few writing errors, while Nivelle is error-free. The song also appears in a younger Italian chansonnier in Bologna, Civico Museo Bibliografico Musicale, MS Q16, written in Naples in the late 1480s. In this version, which has only text incipits, the scribe has probably merged some tone repetitions and perhaps used more ligatures than were in his exemplar.

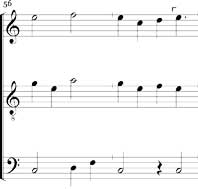

A few details reveal that Bologna Q16 was copied from a French manuscript, which may well have been closer to Busnoys’ original version than the two ‘Loire Valley’ chansonniers. One can notice bar 24, where the countertenor has an awkward leap of a seventh. In this place the note f in Dijon has been skipped making the passage impossible to execute according to the manuscript, while Nivelle has corrected the error by introducing a rest. In Bologna Q16's contratenor bars 38.2-39.1, there is a semiminima rest that shifts the dissonance B (against c'-a' in the upper voices), which in Dijon and Nivelle appears on a stressed beat. Bars 56.2-57.1 are revealing: in Dijon and Q16 the countertenor has the notes Bb-d-A, which in Dijon strongly clash with the tenor’s a'-g'-e'. In Nivelle, the countertenor has been changed to sing d-f-c, which fits with the tenor, which is the same as in Dijon. This error probably goes back to a common exemplar for Dijon and Nivelle, where the tenor’s d' had been skipped, and the missing note value has been fixed by omitting the colouring of the notes a'-g' (see ex. 1)

Ex. 1 Bars 56-57

|

|

|

|

It appears that Bologna Q16 in these passages reproduces a source, which contained the original formulations. For Dijon and as well as Nivelle an exemplar with errors has been used. The Dijon scribe has reproduced it rather uncritically, while the scribe in Nivelle has corrected the countertenor in bars 24 and 56-57 – and possibly at the same time normalized the ending of the couplets (b. 58).

Comments on text and music:

In this elaborate bergerette, the speaker – probably a woman – expresses her confidence that everything will go well in love with the help of the allegorical figures we know from the Roman de la Rose. The negative forces, Dangier, Fortune and Male Bouche, cannot be more powerful than the positive ones, Amour and Bel Acueil.

It is set for two high voices (c’-f’’ and g’-c’’) and a low contratenor (G-d’), often with a great distance between the voices as in the three-part canonic imitations an octave apart, which open the song and appear again at the midpoint of the refrain. But much of the time the upper voices are close together, singing in thirds, see for example bars 4-6 or 14-19. The tenor part is interesting. It has a dual function; when it moves in its low range, from g to g', it functions as a normal tenor part, while in its high position between c' and c'' it functions rather as a second voice in a setting for two equal, high voices. In the unison, canonic imitation, which begins the refrain's third line (bars 30.2 ff), it even crosses above the superius. This disposition of the voices produces a bright sound that is greatly nuanced by the changing function of the tenor, and it is kept mostly within the C- and G-hexachords with only slight colourings to the flat side.

The two sections of the bergerette are in the same mensuration, tempus imperfectum, and there is no great change of harmonic colouring between the sections. The needed contrast in this refined and elegant song is obtained solely by the ductus of the voices. The refrain section is characterized by long expansive lines with much imitation between all three voices, much variation in the sound, and in the last line a discreet solo display in the countertenor of rhythmic empowerment. Against this, the couplets are compact and direct in their presentation of the words, and the tenor remains in its role as a tenor. It is easy to imagine that the song could do well in a performance with the best boys from a maîtrise on the upper voices, while an experienced adult singer took care of the low voice.

PWCH October 2024